Suicide is a selfish act, and Ben was not a selfish person. What finally put him over the edge twenty-six years after he came home from Vietnam, I will never know. He probably didn't even know himself. Ben was my best friend. We had an almost psychic connection. We always seemed to know what the other one was thinking. But this time it failed me. Sometimes I'm afraid he thought I knew what he was planning and that I was condoning it because of my silence. If I have any guilt, it is that I should have known. We both knew what his problem was and that suicide was a possibility. But he was under the care of professionals, and he had a good marriage and a well-paying job. We were doing everything right. So I let my guard down. You can never let your guard down.

Ben enlisted in the Army after he graduated from high school. He wanted to serve his country. He arrived in Vietnam with the 101st Airborne in December 1967. His letters home contained descriptions of the countryside and the conditions, but very seldom his experiences. The one exception was a letter dated February 18, 1968:

We're still in Quang Tri Province. ... The NVA is blowing up the roads and bridges as fast as the Sea Bees rebuild them. We're the only ones that get anything done permanently. We kill people.

Good-bye,

Ben

Ben was shot in the arm and sent home in April 1968. He avoided the V.A. and threw his Air Medal and his Purple Heart in the trash. He started classes at Whittier College, dropped out, went through two brief marriages, and had a problem with alcohol and drugs.

He had never heard of Posttraumatic Stress; he just thought he was going crazy. In the early 80s, he got involved with the Vet Center in Sacramento, a volunteer organization staffed by combat veterans. When he found out there were so many others who shared his symptoms, he told me that knowledge literally saved his life. He had a C & P exam [Compensation and Pension Examination] for his PTSD, and was granted a 10 percent disability in March 1983.

Everything was pretty good for a while after we married in 1985, but about a year later, Ben began to feel depressed, sad, and tearful for no apparent reason. In his room, he had to orient the desk so that he was facing the door, and in public places, he always had to have his back to the wall. He stockpiled food and survival gear and guns. He was having combat nightmares and told his doctor he felt quite certain that he would have killed himself if it had not been for my support.

Ben was put on medication for the first time, and his PTSD rating was increased to 30 percent. We learned everything we could about the condition, and discovered that his symptoms were pretty typical. He began to talk a little about his survivor's guilt. He told his doctor that of the 350 men who underwent jungle training with him and went to Vietnam together as a unit, only 18 of them came back alive.

Ben was put on medication for the first time, and his PTSD rating was increased to 30 percent. We learned everything we could about the condition, and discovered that his symptoms were pretty typical. He began to talk a little about his survivor's guilt. He told his doctor that of the 350 men who underwent jungle training with him and went to Vietnam together as a unit, only 18 of them came back alive.

Four or five times a year, he would have what I called a "spell." It was like he would turn into another person. He would get this edge to his voice, and nothing my daughter Aubree or I did would be right. Finally, he would retreat to his room upstairs, slamming the door. I just left him alone. After a time, he would come out and be very apologetic. He knew I would still be there for him when he "came down."

In January 1993, he spent a month in the PTSD unit at the V.A. Medical Center in San Francisco. I found a note he had written in the hospital that said, "To survive my part of the Vietnam War, I detached myself entirely from what I saw, and completely forgot the battles and the names and the faces of the men I had served with. ... I have come to understand that this type of detachment is not something stepped into and out of easily. It takes time and effort."

In July 1994, I went with some old friends to a family cabin we have on the upper Sacramento River. Ben could not go because of his work schedule. I talked to him on the phone Sunday. He sounded fine. Aubree called me after she got home from work on Wednesday and, when I asked about Ben, she said that the same "Do Not Disturb" sign had been taped to the bedroom door for two days. I asked her to look to make sure everything was all right. She came back to the phone frantic. Ben was on the bed not moving, and there was a bottle of pills and booze on the bedside table. Ben had not had a drink in twelve years. I told her to call 911. Ben knew that Aubree would find his body. I am finding it very hard to forgive him for that.

I don't know when Ben made his fatal decision, but it wasn't spur of the moment. He had gone through financial files and left things in order on his desk. He left me a short but not very revealing note. "Judy, There should be close to $xxxxxx. I'd like to have left you more. I'm at the end of my rope. I love you forever. Ben"

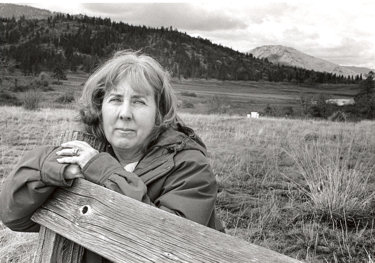

It has been tremendously hard bringing up things that I have been trying to put behind me, but I want people to know about Post Traumatic Stress. I want people to know that there are ways to deal with it, to make it better, but there are no guarantees. We can't guard them twenty-four hours a day. I want to tell survivors that all their "should haves" probably wouldn't have changed a thing. Ben had a privileged upbringing, a good job, and a loving, happy, stable marriage. He had beaten his addictions. We knew about PTSD. He was under psychiatric care and on medication, and I was in constant contact with his medical providers. I thought we were doing everything right. I thought we had everything under control. And still he killed himself.